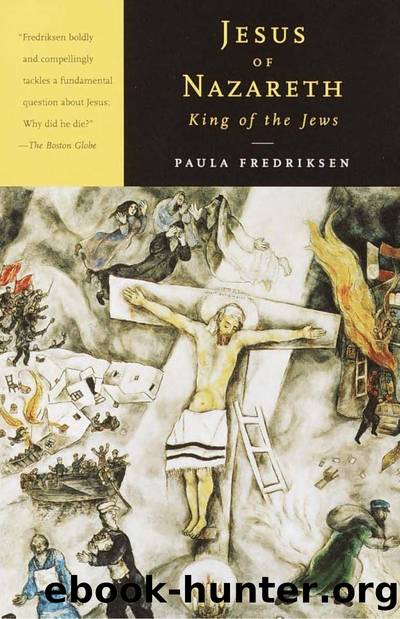

Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity by Paula Fredriksen

Author:Paula Fredriksen [Fredriksen, Paula]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Autobiography, Biblical Criticism & Interpretation, Biography, Christian Theology, Christology, New Testament, Non-Fiction, Religion

ISBN: 9780679767466

Google: LOMC-pDVPmAC

Amazon: 0679767460

Publisher: Vintage

Published: 2000-12-05T00:00:00+00:00

Economics, Politics, and Power

ALL FOUR GOSPELS present Jesus as initiating his mission in the Galilee; two, Luke and John, specifically set some of the mission in Samaria; and all four bring it to a close in Judea, in Jerusalem at Passover. Distilling Jesus’ social context from evangelical tradition requires that we have some grasp of the history that shaped these three regions. We must go back again, then, to events under Assyria and Babylon.

The Northern Kingdom of Israel finally capitulated to the Assyrian invasion in 722 B.C.E. Assyria skimmed Israelite elites off of their native territory, settling them elsewhere within the empire and relocating other peoples there (2 Kgs 17). The empire incorporated these regions—both the Galilee and Samaria—as provinces. Some scholars assume that the larger part of the Israelite population in these areas remained behind; others, that a new population resettled this entire area. On this issue debate continues.

Ancient unresolved conflicts between King David (who c. 1000 B.C.E. had sought to consolidate worship of the God of Israel in Jerusalem) and the northern tribes (who had worshiped at various scattered—and biblically attested—cultic sites) resurfaced in the subsequent history of the region. When in the late sixth century B.C.E. Persia released the Judeans exiled to Babylon and permitted them to return to Jerusalem and to rebuild the Temple, Israelites who had remained in the province of Samaria protested: They already had their own site of worship at Shechem. Later, following Persia’s defeat at the hands of Alexander the Great (d. 323 B.C.E.), these Israelites built a splendid temple on Mount Gerizim that rivaled Jerusalem’s (AJ 11.297; 307–11. Some disaffected priests left Jerusalem and installed themselves in Samaria’s temple). The Gospels catch the echo of this old rivalry. “Our fathers worshiped on this mountain,” the Samaritan woman tells Jesus, “and you say that in Jerusalem is the place where people ought to worship” (Jn 4:20). And in Luke, Samaritans refuse to receive Jesus, “because his face was set toward Jerusalem” (Lk 9:53).

Samaritan religious autonomy suffered and relations with Jerusalem worsened drastically in the period of Judean expansion following the successful Maccabaean revolt. The Hasmonean John Hyrcanus subdued Samaria’s capital city, destroying the temple on Mount Gerizim in 128 B.C.E. before turning south to Idumea (the biblical Edom), which he likewise subdued, forcing the Idumeans to accept Judaism (BJ 1.62–63; AJ 13.254–58; this conquest was the occasion of Herod’s family’s conversion). Later, Hyrcanus’ son, pushing north, secured the Galilee and forced conversion on the Itureans (AJ 13.318–19). This phase of the Hasmonean military and cultural consolidation around Jerusalem went more smoothly than it had in Samaria: The Galilee had no comparable rival cultic site. Nor, evidently, were forced conversions required, perhaps because those Galileans who worshiped the God of Israel, like the Samaritans earlier, represented that Israelite remnant that the Assyrians had left behind.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret Power of Speaking God's Word by Joyce Meyer(3144)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(3116)

Real Sex by Lauren F. Winner(3000)

The Holy Spirit by Billy Graham(2932)

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2515)

Jesus by Paul Johnson(2347)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(2321)

23:27 by H. L. Roberts(2237)

The Nativity by Geza Vermes(2218)

Chosen by God by R. C. Sproul(2148)

All Things New by John Eldredge(2145)

Angels of God: The Bible, the Church and the Heavenly Hosts by Mike Aquilina(1948)

The Return of the Gods by Erich von Daniken(1924)

Angels by Billy Graham(1914)

Knowing God by J.I. Packer(1843)

Jesus of Nazareth by Joseph Ratzinger(1795)

The Gnostic Gospel of St. Thomas by Tau Malachi(1778)

Evidence of the Afterlife by Jeffrey Long(1773)

How To Be Born Again by Billy Graham(1770)